How We Think About "Behavior Management"

“What ‘behavior management’ system do you use?” This is a question we often hear from visiting educators, as well as prospective parents touring the school for admissions. We understand the general impetus for this question, prefaced around wondering whether our classrooms are “well run” or “well behaved” or just based in curiosity with how we “deal” with children who might not be on task in the way we’d like them to be. In many schools, behavior management systems are almost a badge of honor for teachers, proudly displayed as evidence of a classroom under control. And believe it or not, some of us even sat through entire college courses dedicated solely to this topic!

However, the notion of a behavior management system does not square up with our philosophy at Long-View. First and foremost, we do not actually think about “managing” anyone’s “behavior.” We are interested in teaching children to productively engage in the learning process with agency, curiosity, and earnestness, and a system of managing behavior does not serve this goal. So be assured, we are not handing out popsicle sticks or changing cards from green to yellow to red, or giving out stickers, or having everyone sign a contract, or putting demerits on the board. That being said, we are engaged in high-level content, critical thinking, and rich tasks within our classrooms, which necessitate productive interactions, self-management, evolving communication skills, and awareness of one’s impact on the learning environment.

Behavior management systems go hand-in-hand with a top down, teacher-centered pedagogy based on traditional behaviorism psychology. If a teacher is attempting to cover content quickly under a philosophy in which children are “empty vessels” who also have little agency within the classroom, then a system to cleanly manage behavior, rewarding those who are compliant and punishing those who distract, is in order. Gimmicks like desk pets, token economies, and clip charts don’t help schools to cultivate, and may actually diminish, a high quality, challenging, rich learning environment like what we strive to foster at Long-View. While productive behavior is a goal, it is equally important that children learn to regulate themselves, assess their behavior against communal norms, and earnestly press towards deep learning.

Therefore, our goal is for students to actively explore, collaborate, problem-solve, and persevere because they want to—not because they’re being controlled by an external system. As we design learning experiences, we think about many factors, shooting for a rich experience that doesn’t shy away from complexity, while also helping learners build from what they know.

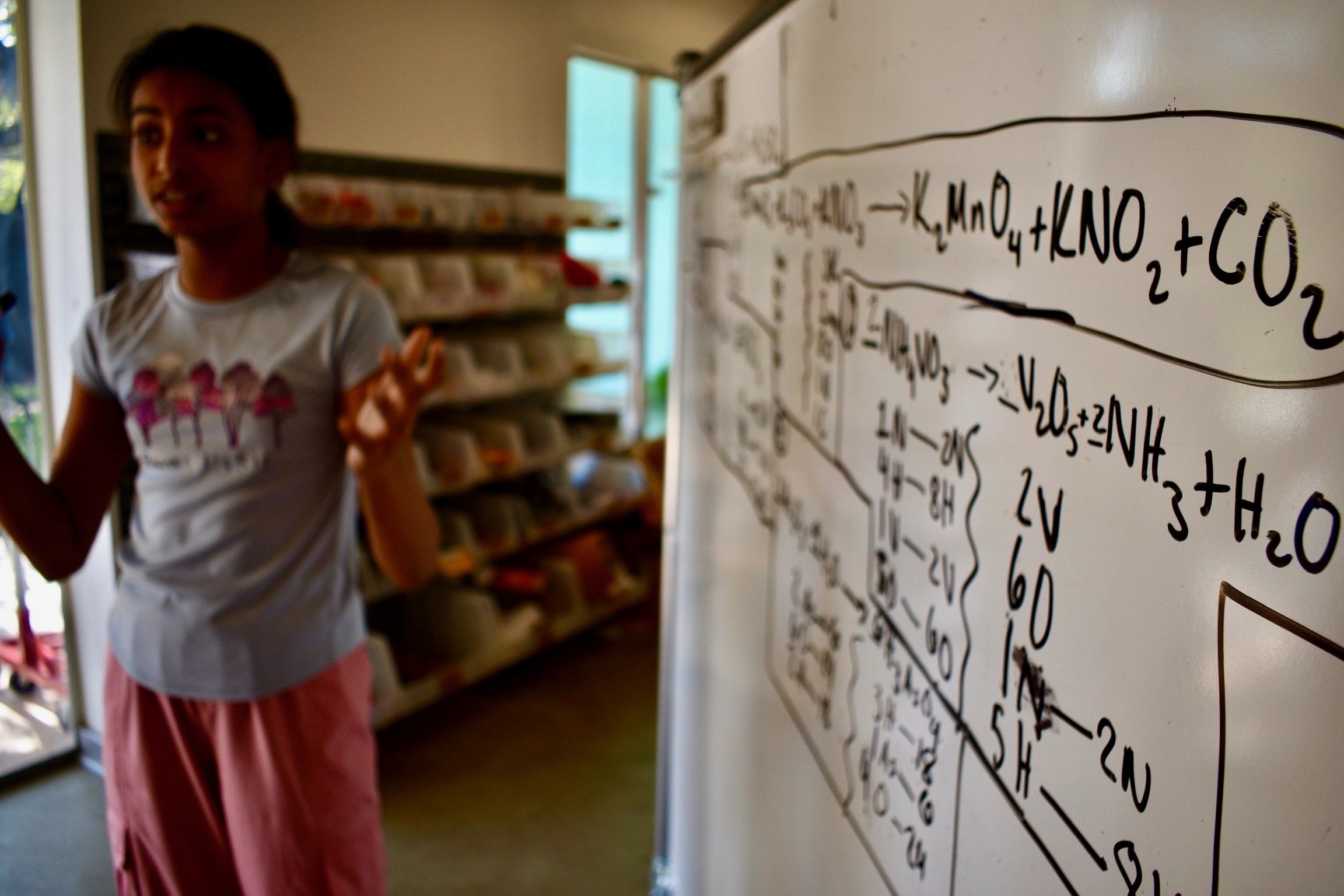

Content plays a key role in this process. We focus on presenting material in the most interesting, high-level way possible—something that would engage even an adult learner. For instance, instead of drilling single-digit addition with our second graders, we teach them about unitization, guiding them to understand “the count” and to see terms within an expression. Rather than using an acronym to help our middle schoolers structure an essay and using a worksheet to practice, we study the craft moves of effective authors and push our young writers to plan, draft, think, revise, seek feedback and keep striving to improve work over time, just as published writers do.

Let’s be clear: we aren’t aiming to entertain. We don’t design “math games” to trick students into learning without them even realizing it. We don’t view content as so boring and dry that we have to find a way to “make it fun” and distract or compel children to inadvertently learn. Entertainment is fleeting, and when it ends, behavior often derails. More importantly, if we want to cultivate thoughtful, reflective, and curious learners, “tricking” them into learning is not the way. We take issue with classrooms that try to force engagement in low-level and unchallenging material with silly games, bells-and-whistles, or rewards.

In addition to content, we think about how learners spend their time, aligning their experiences with how experts in the field work. We prioritize learner agency, allowing children to make choices and take ownership of their learning.

We think about culture and continually nurture this culture; we work hard to establish a culture of learning, interest in the world, and self-direction while being community minded. Instead of managing behavior, we focus on teaching learning behaviors; we explicitly teach these behaviors to the group and then hold individuals responsible.

Ultimately, we recognize that we are working with children—young humans who are still learning and growing. When behavior concerns arise, we ask ourselves: “What might these outward behaviors be telling us about what the child is working through internally?” If we see a pattern, we have a conversation with the child, just as we would with any human being. We hold positive assumptions about the intentions of that child, while also coaching the child into mindsets and behaviors that could be more beneficial. Inviting a child into the problem-solving process is another approach we take. We work hard to minimize “top-down” requests, but, as the adults, we do point out when children should make different choices or change something. And, if necessary, we communicate with the child’s parents and work together to move that child forward as needed.

At Long-View, there is a deep philosophy behind everything we do, from how we design learning experiences to how we address challenges. We aim to honor the authentic human experience and embrace the complexity that comes with it. So the next time you visit a school or speak with a teacher who uses a behavior management system, we hope you might ask them: “Could you tell me more about why? What’s the philosophy behind that?”