Curating a Diverse Library for Our Learners

Here at Long-View, the members of the Literacy team tend to moonlight as librarians. Whether during the school year on Thursday afternoons, early in the morning, or during the summer months, we are constantly expanding, curating, organizing, and pondering the Long-View library collection. In recent years, Long-View has particularly committed itself to enriching the diversity of the books we offer our learners. While the push for more diverse books—especially for children and teenagers—has become a major initiative across the education and publishing worlds in the United States only relatively recently, it’s much more than a fashionable trend. And it’s much more than an empty gesture towards inclusivity.

First, though—what does that oddly vague phrase “diverse books” even mean? Certainly it means books in a plethora of genres and forms, covering a vast array of topics. But in the context in which it usually appears, it aims specifically to center groups that have been historically marginalized by American society as a whole and that continue to be underrepresented within the publishing industry due to systemic prejudice.

The importance of a diverse reading diet has probably been explained best by Professor Rudine Sims Bishop as far back as 1990, through her famous metaphor of “mirrors and windows.” All children need to read books (both fiction and nonfiction) whose characters and stories serve as “mirrors” to their own identities and experiences—this supports children’s identity formation and helps them develop a crucial sense of self-worth (which is even more important when the larger society sends messages that seem to deny it). At the same time, kids need books that offer “windows” into the lives of people who look different from them or have different backgrounds and life experiences. This can help kids grow their empathetic imagination, increase their awareness and understanding of others, reject stereotypes, and become more open-minded, open-hearted citizens of the world. This, in turn, lays the foundation for a more just and flourishing democratic society.

Once we understand books as vehicles for these lofty goals (above and beyond their more obvious benefits), it makes good educational sense to choose books for our library—and, for parents, to select books for your children—with an eye towards representation. But this still leaves us with some important questions.

Should we be choosing books with protagonists from diverse backgrounds or books written by authors from diverse backgrounds? Many have argued that priority should be given to “own voices” novels, i.e. those that fit both categories: novels about characters from marginalized groups whose respective authors come from those backgrounds themselves. The “own voices” movement, sparked by YA author Corinne Duyvis in 2015, has helped dramatically improve representation, lifting into public view countless new voices and stories that the publishing industry once deemed “unsellable” and delivering brilliant, true-to-life windows and mirrors to children across the country and beyond. But it has also carried with it the danger of pigeonholing authors from marginalized groups—creating a climate that can pressure them to write only about their own identity and persecution, and occasionally even to reveal aspects of their identity they don’t wish to share for the sake of proving their authenticity.

The challenge for teachers, librarians, and parents is related. When building a diverse collection, we always have to be mindful not to flatten excellent books to the point where we are buying or celebrating them mainly for their representation value and overlooking their literary qualities. We need to avoid a kind of “check-the-box” mentality that tokenizes authors from underrepresented groups and actually perpetuates some of the very problems the diverse collection was meant to address in the first place. That is the type of thinking that can turn “diverse books” into a genre or shelf or unit of its own, rather than a parameter that applies across the entire library collection.

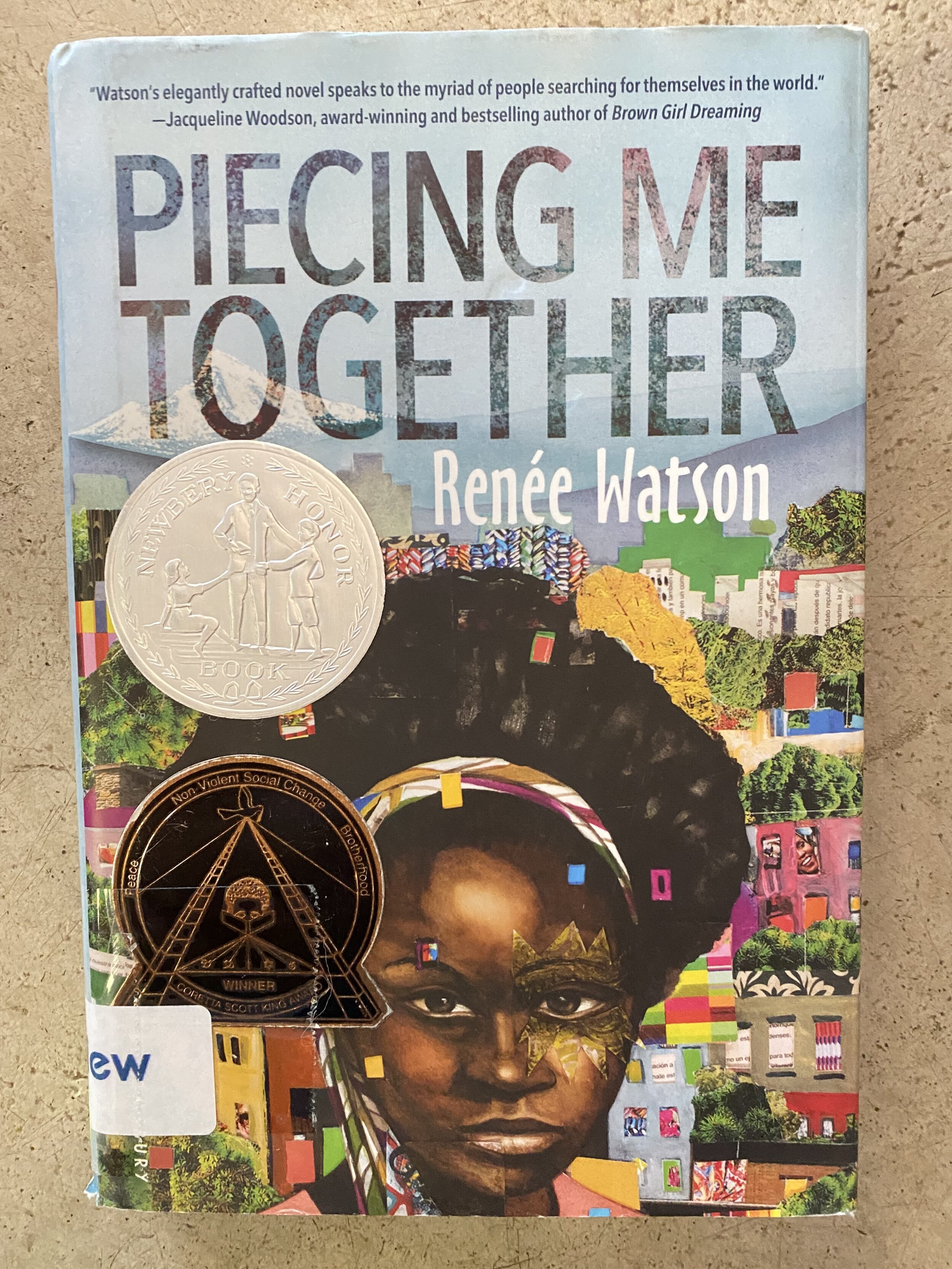

At Long-View, we try to avoid these pitfalls by thinking critically about how to build our collection in the best interests of our learners. Rather than seeing representation as a selection criterion in a vacuum, we combine it with others: for instance, we may realize one band needs more top-quality middle-grade novels for an upcoming historical fiction unit, or we may learn from a library-focused Campfire discussion that our older learners crave more YA fantasy, so we search for the absolute best ones that also feature diverse representation. Often this leads us to “own voices” books. We think similarly when it comes to building individualized summer reading lists for our learners as well. Sometimes, though, we do search directly for books with a certain type of representation because we know a specific learner really needs to see their particular experience reflected in a wonderful character.

Ultimately, learners deserve books that offer rich educational experiences on multiple levels and dimensions at the same time. Rudine Sims Bishop pointed out that, just as you can sometimes see your own reflection in a window, “window” books can end up transforming into “mirror” books, revealing to young readers the essential humanity that connects all of us. We believe Literacy teaching should always aim as high and far as that. It’s just another part of taking the “long view.”